Do these two statements contradict each other?

- The shortest distance between two points is a straight line. ~Archimedes

- There are no straight lines in nature. ~Antoni Gaudi

Archimedes is arguably one of the smartest human beings to have ever lived, and I mean that with absolutely zero hyperbole. He’s most commonly known for shouting “Eureka!” as he got into a bath as he realized the amount of water displaced from the tub was equal to the volume his body occupied, and for the water screw which is still in use today in many places.

In the late 90’s a book sold at auction for $2,000,000 was discovered to be a palimpsest containing 7 treatise written by Archimedes, and two are the only known copies of those works in the world. Researchers also discovered that Archimedes was not only familiar with the concept of infinity, but he outlines seven types of infinity. SEVEN.

- On a geometric plane it can extend in both directions to infinity

- There can be an infinite number of points on this plane

- The number of straight lines drawn between two points are infinite

- There are infinite numbers of curves possible between any two points

- etc. etc.

It’s a fascinating story, and if you’d like to learn more about it, you can check out the Archimedes Palimpsest Organization.

This from a man who lived from 287 – c. 212 BCE.

Abstract Reasoning

What made his mind so unbelievably powerful was his ability to use logic and reason to intuit solutions in the abstract mathematical world. His strength was using his imagination to reason his way towards understanding universal truths.

With this approach, he was able to discover timeless truths about the world, and build his understanding on rock solid foundations built on logic & reason. It’s an incredibly powerful ability to pull order from absolute chaos. This is the way of fighting entropy and decay; find answers that are beyond the mere considerations of this broken-down world we live in; truth lives in a universe beyond the scope of time & space. This is the world of First Principles.

But, What About the World of Gaudi?

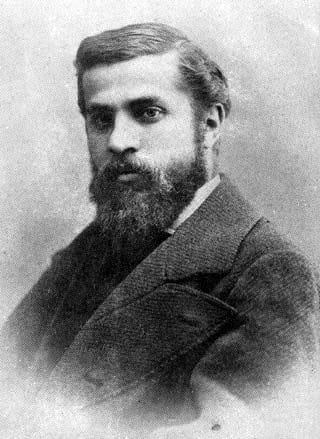

Antoni Gaudí was an architect born in 1852, and died in 1926. His buildings look like Dr. Seuss drawings brought to life, and they’re absolutely gorgeous. If you’d like to see examples of his work, click here for a Google image search.

His work “Sagrada Família” in Barcelona looks like a sand castle brought to life, and it will be finished 100 years after his death. It’s a testament to the enduring power of his work.

He recognized that in the world of nature, there are no straight lines. Even the unerring line of the horizon is actually a curve so large it only appears straight to us.

And there lies his genius.

Gaudi lives in the realm of nature. In the real world. Archimedes lives in the realm of abstract mathematics.

The world that human beings live in never moves in a straight line. It’s curved. It’s messy. It’s pure chaos.

The World of Chaos

This fundamental truth about the world we live in is the reason why the most elegant, simple answers lack mathematical beauty. They twist, they turn.

In the real world, indirect is more effective than the direct.

Success is usually the byproduct of aiming at something else. The straight line approach is often the longest way to get somewhere.

Training Artificial Intelligence

There’s a fascinating exploration in the world of AI that shows us this counter intuitive truth.

Researchers built systems that were allowed to play inside their environment without any specific goal or outcome; it was given free reign to discover what it could do on its own.

Later, researchers would establish a specific goal and see how long it would take the system to achieve it. After that, they would increase the difficulty by introducing a variety of obstacles and challenges.

The AI system took longer in the second case to achieve the goal, but was still able to do what was asked of it.

The Wrinkle

Here’s where things got interesting: AI systems built specifically to complete the task were almost completely unable to accommodate the simplest obstacle or challenge.

The most direct approach (design the tool to do the task) wound up being the least effective when presented with anything other than an optimal environment. The roundabout solution (design the tool to play on it’s own) takes more time & resources, but winds up being profoundly effective even in the face of insurmountable difficulty.

Our World

You might live in a perfect fairy tale world, but I sure as hell don’t. I face challenges, obstacles, and frustrations every day.

That’s why the direct approach rarely works in any context; whether it’s in relationships, a physical confrontation, business plan, marketing, or any other situation involving humans.

In ideal situations, yes, the abstract world of logic & reason will serve you well. But, we live in a crazy, chaotic swirl of doubt and uncertainty.

That’s why success is often the result of trying something else.

Want to make tons of money? Don’t focus on making money. Focus on solving peoples’ problems; the money will follow.

Want an amazing romantic partner? Don’t focus on finding someone. Focus on being an incredible person who has a lot to offer, and your match will show up.

Real World Success

Whatever you want to do in life, don’t aim at it. Look to what naturally creates that successful outcome, and then focus all your energy on that.

Live in the beautiful, organic, curvy world of Gaudi, not the world of Archimedes (no matter how much you love clean lines).